My friend got up at 4 am on Thursday, 13 January. If he set an alarm, I didn't hear it. There was no water on our ground floor. But there was water in Shore Crescent, to the side of our house. In all the talk of local flooding, I had always imagined that the water would come along Waterline Crescent directly from the river overflowing its bank to the west of us. But no. It spilled out of the storm drains, fed by the water in the newly filled creek to the north.

I got up two hours after high tide and went downstairs and into the street (below). The water had been higher. There was currently no way back home for our smart but largely impractical (at times like this) Audi A4 which my friend had parked up a hill the previous afternoon.

The river had peaked at 4.5 metres (at the Brisbane City gauge), almost one metre lower than in 1974. There was a collective sigh of relief in many suburbs, including ours. It had been expected that the river would reach 5.2 (1974: 5.45). There were still, however, 67 suburbs with properties that had been completely flooded; very many businesses wiped out across the city; roads structurally compromised; and hundreds of thousands of homes without electricity. The death toll was still rising as state emergency services personnel went about the grim task of searching damaged properties in the Lockyer Valley – and further afield – as flood waters receded and debris beached up the coast.

Despite all the hoo-hah about Australia's third-largest city, one of the hardest-hit places has been the small community of Grantham in the Lockyer Valley, where most of the 20 victims of Southeast Queensland's floods lived. Grantham's 370 inhabitants are still evacuees, not having been allowed back to their homes as wreckage-sifting SES workers may yet find more bodies. Twelve people are still missing.

We were confident that the river wouldn't peak any higher with that afternoon's high tide, so by mid-morning we started gradually carrying stuff downstairs again. I went to my Pilates class in an attempt to restore normalcy (I will never complain that the aircon is too chilly again): my friend went to retrieve the car and to buy ice. Many of the roads in neighbouring Hawthorne were flooded and closed, but the water in our immediate vicinity was receding rapidly.

A continuing lack of power meant supper preparations before nightfall and early to bed.

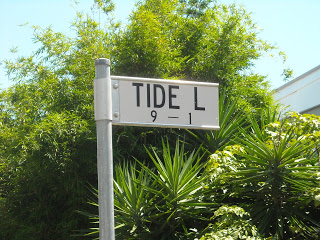

By the way, in case you've missed the joke before, this is where we live.

On Friday my friend returned to work: the tunnels had not been flooded. And on Friday, as promised by Lord Mayor Campbell Newman, the clean-up began. Mud-scrapers and brushers, debris gatherers, street-cleaners, sandbag collectors – they were out in force in a myriad small trucks and utes.

There was a low point when, having texted nearest and dearest back home in the UK that we were safe and dry, the battery on my mobile was almost drained. We still had no power (although Oxford Street was reconnected yesterday) and I felt very cut off. But when I went to the supermarket, they charged my phone on the desk while I did my shopping. And a lady in the queue for coffee at the Deli told me the library had Wi-Fi. Things were looking up.

Since Wednesday we'd been eating food from the freezer before it perished: tonight was no exception. Then, much as we love candlelight, we ventured up to Oxford for some light and life, our neighbours still largely absent because of the lack of power. And we were relatively late to bed – oh, it must have been nearly 10.

On Saturday the city-wide clean-up continued apace, this time augmented by thousands of volunteers. There were people everywhere – Council workers, volunteer organizers, water company people and, to our great delight as we returned from a fruitless search for gas lamps, Energex technicians. We were finally reconnected to the power supply on Saturday afternoon. What a relief. There was still much to carry downstairs, and neighbours once again came to our aid.

On Sunday, yet more clean-up volunteers took to the streets all over the city, muddied but unbowed. The evening was calm and lovely, so once more we took a beer and went to gaze at our river. (This might become a pre-sunset habit.) To look at the water, you could never have imagined it a cruel, raging torrent. I had to take the concluding comparison photograph, but I couldn't stop there...

One consequence of Brisbane's recent trauma that will impact on us most is the loss of the CityCats and City Ferries. Although most of the boats were moved to safety before the flood, the terminals have taken a bashing. Living in a waterside suburb, we use the ferries several times a week; to go to the market at New Farm, to cross the river for running or cycling along the north shore (and on the floating Riverside Walkway, which was also washed away), to go into the city for shopping or the evening, and to give visitors to Brisbane a pleasant introduction to our home town.

Busy Bulimba ferry terminal, August 2010

Over the last five years, the CityCat service had been expanded, with new vessels and many more passengers. Thousands of Brisbanites use the ferries each day to get to work. It is an extremely efficient system as well as a symbol of this city's ambition. There has been a dearth of information about the ferries' fate over the last few days, except this sign at all terminals.*

Ultimately, of course, we were extremely lucky. Many people in regional Queensland to the north and west of Brisbane, and in lower-lying suburbs of the city, were not so lucky. Many Queenslanders complain that there is undue focus on the southeast of the state, and especially the state capital: but the fact is, Brisbane means more to people on the other side of the world than Goondiwindi. Several friends in the UK, however, commented on how alarmist was foreign reporting of Brisbane's woes. Perhaps they imagined that what happened in Toowoomba and the Lockyer Valley was also happening in the city.

Our internet connection was re-established on Sunday. I was shocked to learn that more than 600 people had died in mudslides in Brazil while Brisbane was waiting for the river to rise. I don't remember that even being mentioned on the national and international news bulletins 'on the hour every hour' as my ears were glued to my local radio station. I hope I'm mistaken.

* The following day, Lord Mayor Campbell Newman announced that it was going to cost between $70 million and $100 million and take between 18 months and two years to restore the service.