River of tears

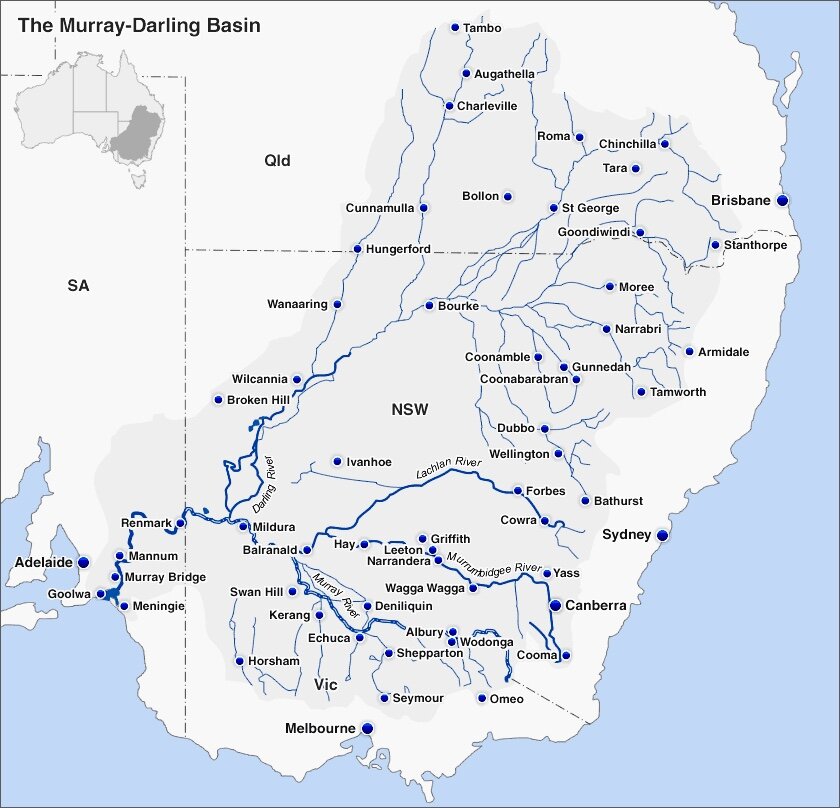

By now, ten years ago, my friend and I had decided to move to Brisbane from the UK, and were awaiting approval of our visa applications. We were given lots of advice about living in Queensland, including a warning from a helpful Irishman to avoid conversations on three topics: daylight saving; Aboriginal disadvantage; and the Murray-Darling. I wasn’t surprised about the first two, being used to debate about Scottish farmers and clocks going backwards and forwards, and aware of the struggles of Australia’s original inhabitants. Surely the third on the list, Australia’s largest and most complex river system, couldn’t be as provocative?

How prescient was our Irish friend? Last week I was petitioning outside my local council offices in Melbourne. A couple approached me and, completely ignoring the merits, or not, of Bayside City Council declaring a climate emergency, asked me if I had heard of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan. They were very angry that water was being held in a storage lake upstream from the junction of these two major rivers and not being released to farmers.

The Murray-Darling Basin Authority was established in 2008 and defined as the principal government authority charged with managing the Basin in an integrated and sustainable way. For the first time, the river system was to be managed as a whole rather than state by state. The Murray-Darling Basin Plan (MDBP) was proposed to address the problems of over-allocation of water, prolonged drought, and climate variability and change. The solution was to increase environmental flow in an attempt to support river ecosystems. Alas, many of those ecosystems are now collapsing.

I remember heated debate and the burning of copies of the Plan in the streets of bush towns. It would almost be laughable how such noble intentions could fail so miserably if the fall-out was less of a disaster for the Murray-Darling, and the Darling in particular. A prolonged severe drought, irrigators’ greed, governance still divided between federal and state, and a stubborn disregard for a rapidly escalating climate crisis among inherently conservative communities and their political representatives have all contributed to produce virtual paralysis in response to an impending catastrophe. Waterless towns and putrid rivers over a huge region and across state boundaries are but a blink away. I do not believe I exaggerate.

I struggle to imagine that water-buy-back rorts and seriously degraded water courses could not have been foreseen and forestalled before a million fish perished near Menindee in southwestern New South Wales, and we saw old men’s tears fall upon the rotting bodies of decades-older, irreplaceable Murray cod. It’s relatively easy to be angry about this state of affairs but far, far harder to dispel despair.

Many of the Murray-Darling’s problems have been created over decades, but the most recent escalation began to unfold in December 2018, when 10,000 dead fish were found along a 50 km stretch of the Darling near Menindee. Less than a month later, a huge fish kill occurred. Three years ago the Menindee Lakes were full. Now they are empty: I have seen them dry and desolate: I have stood on the Darling’s dry riverbed downstream of Menindee, on Tolarno Station. There can be fewer more heartbreaking sights than the remnants of huge River Red Gums collapsed down the steep banks of a once-deep-flowing waterway, their massive root systems unable to reach even green fetid pools of what is left of the Darling. Or a town silently suffering as its source of tourist revenue evaporates.

Fading foliage

You can read the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries’ account of recent events here. ‘Thermal stratification’ of the water may well have played a role. Few people on our travels, however – from the farmer’s daughter behind the bar at Mungo Lodge, to a lady in the New South Wales National Parks Office, to several artists’ works in Broken Hill’s galleries – mentioned or depicted that particular culprit. They were more likely to cite gross water mismanagement and incompetence at all administrative levels; excessively thirsty cotton; climate-change denialists; a removed, uncaring government in Canberra; and corruption, just about everywhere.

One comment that stays with me was that of the Pooncarie farmer’s daughter. She explained that drought has always caused the Darling to dry up temporarily, but that this time it’s different: few locals expect the river to flow normally ever again. What a terrifying and heartbreaking prospect.

And flooding rains will return eventually… won’t they?

We left Mungo Lake on day 4 of our mini outback trip at the end of August. Scrubby vegetation soon gave way to an empty, desolate landscape.

But things were to get much worse. Suddenly we were amidst total devastation: mile after mile, as far as the eye could see on both sides of the road, of what appeared to be wanton tree-clearing with no sign of purpose: piles of debris left where trees had been slashed.

Nearer to the Pooncarie Road, we discovered a possible reason for the land clearing. How much water do you reckon you’d need to transform the landscape above into the paddock below?

The lower Darling has been the lifeblood of the traditional owners of the land, the Barkindji people – for whom the Darling is the Barka – and, from the mid-19th century onwards, of land holdings established by British settlers. William and Ross Reid established Tolarno Station in 1851, eventually running more than 300,000 sheep over 1,100,000 acres. By the 1870s, a fleet of paddle steamers was carrying wool to Adelaide for export, mostly to Britain. And here, in 1860, Bourke and Wills enjoyed a last hurrah here before their expedition divided at Menindee.

In the 20th century, Tolarno Station had several owners before Albert James McBride bought it in 1949. It remains in the McBride family today. Rob McBride and daughter Kate campaign hard for better management of the region’s precious water (see Tolarno Station’s Facebook page.)

The river hadn’t failed in 150 years before 2015-16, when a 500 km stretch of the Darling was dry. There was average rainfall both those years, so this was not because of drought. The McBride family attribute it to ‘corruption and disruption of the river system’. The river has always watered their sheep, washed the wool, and supplied the homestead with water for washing and drinking. In the dry-river era, the station is dependent on ‘Menindee water runs’ – council supplies of treated, filtered water the McBrides claim is undrinkable – and it don’t come free. We were told of plans for a bore on the riverbed and a 37 km pipeline to a tank where their sheep and goats can drink.

We found some life around the riverbed at Tolarno. There were even some pelicans by a pool on a bend as we arrived, but they are shy by nature and soon skedaddled. We were unable to locate them: the pools reduced as we got further from the homestead.

Left, from top: Australian Wood Ducks; Willy

Wagtail; Monitor Lizard (and above in close-up )

Other creatures had been less fortunate.

Where the pelicans were

View upstream from the riverbed

We moved on from Tolarno to Menindee, where there seemed to be little life. Months ago I’d called the Visitor Information Centre who told me there was no water in the Lakes. I adapted our outback tour accordingly so that we’d spend a few hours there rather than stay over. The Visitor Centre was closed now. A sign directed us to a neighbouring cafe, where a frazzled cook doubled as travel advisor. I wanted to know why Lake Drive was closed. I’d planned to eat our picnic lunch by Lake Menindee, even if it was waterless. It will be to my lasting regret that I didn’t get a picture of it, but I’d learned at Mungo that one dry lakebed looks very much like another. So, here’s one I photographed later – Lake Pamamaroo.

Menindee Lakes is a natural ephemeral system filled from time to time when the Darling is in flood. The lakes are large and shallow, so the rate of evaporation is considerable, a fact that supports the argument that water should be used when it’s available rather than holding it back. Since the 1960s, however, the lake system has been engineered, by means of regulators, into a man-made water storage system that can hold water and release it downstream as needed. The management of Menindee Lakes is shared by the MDBA and the New South Wales government. In summer 2014-15, the Lakes were drained to meet South Australia’s water requirements downstream. Balancing water needs over a considerable area during ongoing drought proved a recipe for disaster on the Darling.

There was water in the river at Menindee itself, however. For a moment it looked almost normal, until you realised it wasn’t flowing.

Is this where the pellies had come from Tolarno? Is it the only decent water hole for miles around? There must have been fish in it, too, because we were privileged once again to witness pelicans’ synchronised fishing.

At first the fishing party was only four.

Follow the leader… then DIVE!

Then four became five…

…and finally a tightly knit pod of six.

This was the most joyous thing in Menindee. For the most part, it was deathly quiet and there was grim evidence of a town that has lost its reason to be.

A deserted, dilapidated caravan park

As directed by the man grilling burgers, we went to look at Lake Pamamaroo before leaving town.

Menindee is only an hour away from Broken Hill, which is another story. But in this famous mining town we came across several striking examples of artists making a point about the sacrifice of a great river to greed, or the degradation of landscape by those with little care for country.

My Darling has been ransomed by Clark Barrett

Ngemba Country 1 by Paul Harmon

Barkandji Country by Paul Harmon

Paul Harmon described his WaterMarks exhibition at the GeoCentre as examining ‘the tension that exists when a stark beauty from the air [his photographs are taken by drone] meets ugly truths on the ground of stolen lands, stolen water, inappropriate land use and environmental degradation’.

You cannot talk about water in the Murray-Darling system without examining ‘the ugly reality of the open water market’. The same legislation that created the MDBA, the Water Act of 2007, also provided the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) with the important role of developing and enforcing water charges and water market rules. The Water Act was the work of the Department of the Environment, as you might expect, but in 2015, the responsibility for water policy and resources was transferred to the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources. Was this the moment when environmental flow began to lose out to cash-cropping?

Anyway, back to the water market. It was well-intentioned enough: to give farmers more options to obtain water, and make it easier to access for the highest-value use. Incredibly, no one seemed to think much about the effects that long years of drought would have on the market. A dairy farmer might have paid $40 a megalitre for his water once upon a time, but 2019 has seen prices as high as $800 a megalitre.

An unintended consequence is the sale of water entitlements. A water entitlement is an ongoing property right to an exclusive share of water from a water resource as defined in the relevant water management plan. (A water allocation is the amount of water released by a state or territory to entitlement holders each year.) As drought has tightened its grip and water resources have deteriorated, some farmers placed their permanent water entitlements up for grabs, in the belief that they would be able to acquire temporary entitlements at a future date when water availability improves. And so it was that water entitlements fell into the hands of non-irrigators, otherwise known as speculators, who hoard their water until they can profit from rising prices, as a result of worsening drought, for example.

What is the extent of corruption in the water market? Must farmers adapt to the free market to the extent of trading in temporary entitlements for their water supplies? Are non-irrigators the only villains of the piece? Does rain-grown (or dryland) cotton as part of rotation cropping address the demand to grow high-income crops? How can we expunge once and for all a belief still lingering in conservative circles that raping the land for its resources is a god-given right? To what extent is environmental degradation deliberate? And, the hardest question of all, when is the drought likely to break?

On 16 October came reports of yet another fish die-off, in the water remnants of Lake Pamamaroo. On 19 October, the Prime Minister (Scott Morrison) claimed that drought is the Coalition’s top priority, with ne’er a mention of the climate crisis. I ask, when will this nation’s water woes become their water wars?

Making the point in Menindee

I am indebted to environmentalist, photographer and writer Sarah Moles, who suggested I visit Tolarno Station; the McBride family for allowing me to photograph the Darling on their property, and their station manager for pointing us in the right direction; The Silly Goat cafe, Broken Hill; outback artist Clark Barrett (www.facebook.com/clarkbarrettartist); landscape photographer Paul Harmon (thinkingpictures.com.au); the MDBA for the Murray-Darling Basin diagram; and all those people along our way who shared their thoughts on this most important subject.