Straya’s second-most-famous Rock?

After several days in Albany on the south coast of Western Australia, we travelled via Denmark to Gnowangerup for a night, then on to Hyden for two days to marvel at spectacular Wave Rock.

There is an almost dead-straight road across WA’s Wheatbelt: Tie Line Road bisects the satellite image below. In surveying, a tie line connects control points on a survey line, helping to maintain accuracy. I’m liking the dark green and dusky pink.

I’d been hoping, en route to Hyden via Lake Grace, that there might be shallow water to either side of us as far as the eye could see. A fellow traveller somewhere recently had speculated there might even be water across the road, but no such drama. We stopped for lunch by Lake Grace North in an understated-pink landscape with strange encrustations protruding from the silt.

Lake Grace is part of a chain of salt lakes stretching more than 100 km from Pingrup to Kondinin. The chain of lakes was once part of an ancient river system dating back millions of years. The climate became drier and more seasonal about five million years ago, with the result that rivers shrivelled into ephemeral lakes dotted about, or disappeared underground. As water evaporates from shallow surface water features, their salts – deposited and dissolved over eons by wind and rain – are left as a crystalline crust.

Lake Grace North

Shadowing Salmon Gums, the region’s most iconic trees

Wave Rock, about 340 kilometres east of Perth, is well worth a visit. It may be out of the way if you’re touring a lot of Australia in a limited time, but just make it happen. Having said that, it’s easy to underestimate distances, especially in Western Australia, the largest state. Build flexibility into your itinerary – not everything will be as you expect to find it – and calculate distances accurately to avoid having to jettison key must-sees. Whatever you do, don’t dump Wave Rock.

We reached Wave Rock Campsite in time to sneak a peek at the Wave before settling for the evening. It is huge and impressive, like nothing you’ve ever seen: water running down its curved surface enhances the smart colour combo. The stripes are created by chemical weathering; specifically, by rainwater runoff dissolving different mineral constituents.

Back at camp, we battened down the hatches in the cold. We had an en-suite shower – a rare treat when camping – which we were able to heat with our small fan heater. Some fellow-campers congregated around a fire pit until almost-freezing. They’re hardy, Aussie campers. Or nutters.

This huge granite cliff is 45 metres high and 110 metres long, and looks for all the world like a wave about to break on shore. The cliff is the northern edge of a much larger structure, Hyden Rock, an inselberg, usually defined as an isolated hill rising above a flat plain. But the massive base structure was underground 60 million years ago, before tectonic and erosive processes imperceptibly lifted and sculpted and eventually revealed.

Water-holding holes (gnammas)

Waterfall

Rock gardens…

Wave Rock was put on Western maps as recently as the mid-1960s, by amateur photographer Jay Hodges. He’d been staying on a friend’s farm near Hyden, and later entered a picture in a competition at the New York World Photography Fair. It was a relatively short leap from success there to the cover of National Geographic.

The local Nyungar (Noongar) people, in contrast, have inhabited this region for tens of thousands of years. Their name for this geological wonder is Katter Kich. It was a meeting place and dancing ground. Ancient handprints can be seen in Mulka’s Cave at The Humps (see below).

Visitors can choose between Wave Rock Walk, 650 metres there and back from car park to the foot of the Wave over flat ground; and Hyden Rock Walk, from an old quarry at the western end, and including some steps, up on to the Rock. Make climbing easier and safer by wearing shoes, not flipflops (thongs), which you’d think would be obvious to climb a rock face, but no. We chose Hyden Rock Walk.

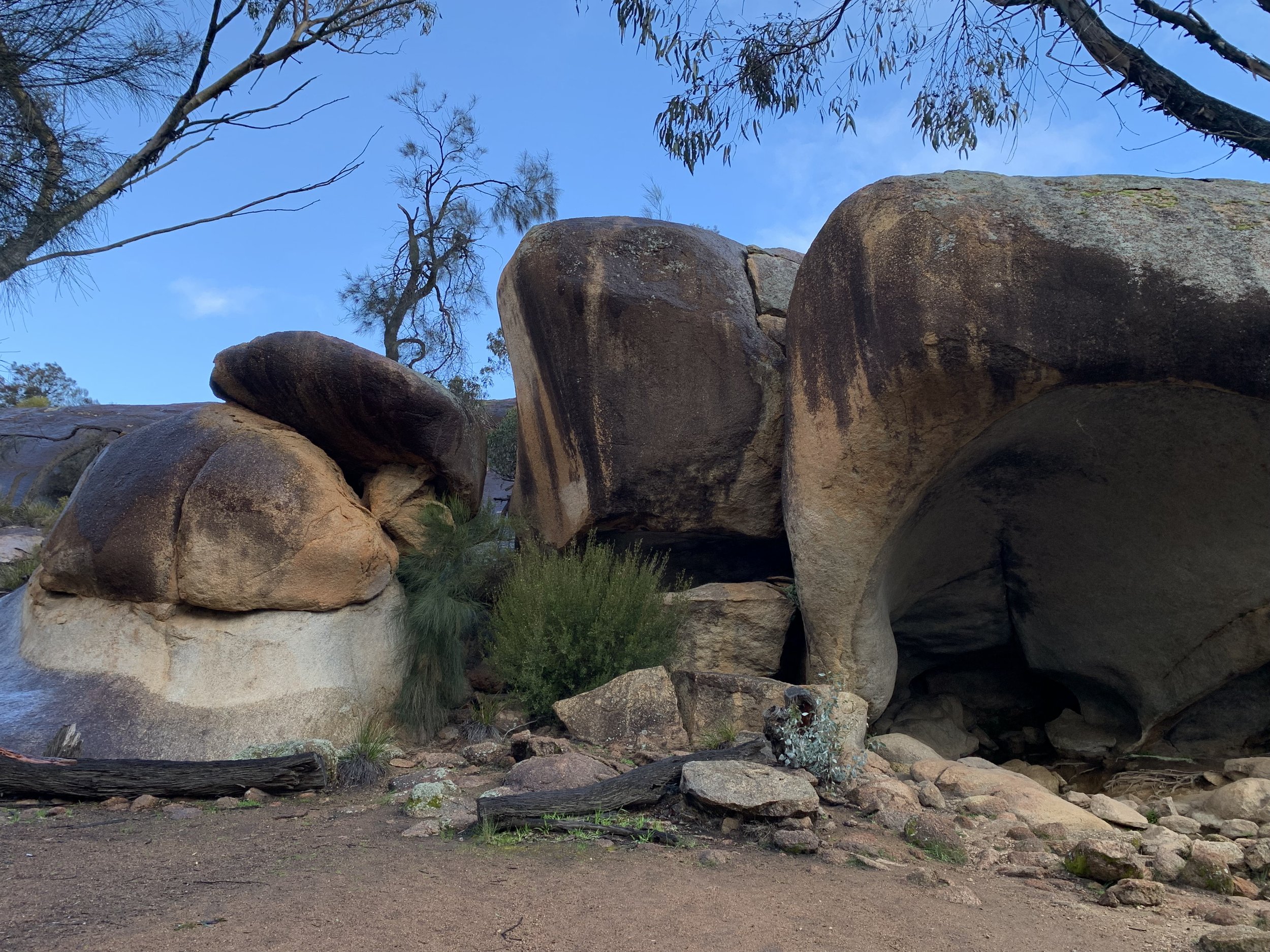

East of Wave Rock is the much less well-known Hippo’s Yawn, essentially a granite cave among She-oaks rather than underground. A couple of short sharp showers interrupted the blue: we sheltered inside the Hippo’s mouth.

A 15-minute drive north of Wave Rock are The Humps, where we went next morning before heading west. Here there were gently shushing She-oaks and serried granite standing stones.

Man in a tafone

There are a number of explanations for the formation of a tafone, both physical (mechanical weathering) and chemical (atmospheric or biological). Tafoni are cavity-like features that form in steeply sloping granular rock, and vary greatly in size. This was a great big boulder balanced on a much, much larger rock.

At one point during several days in the Wheatbelt, my friend gazed across the landscape and mused: ‘That could be Surrey’. He wasn’t wrong, except that the paddocks are huge and consistently flat. They’re also increasingly yellow rather than green or straw-coloured, which the old geezers in the pub in Gnowangerup explained was Aussie farmers cashing in on the crash of Canadian canola. The bursts of yellow are stunning, with a hint of not-quite-rightness.

From Hyden to Brookton was 250 kilometres. Brookton was bigger than expected but the council-run campsite contained a single large caravan showing no obvious signs of life. It was flying the Aussie flag, which I had come to realise meant permanent occupant or temporarily local FIFO worker. We ate rice and the last veggie burgers. This wasn’t the first time – and wouldn’t be the last – that I felt as if we were among few people left on earth, or certainly in this part of it.

Travelling in the time of covid. Sometimes you strike gold.