Outback 2: back o' Bourke

At last, we were going to be back o' Bourke, literally. Both last year and this, we had been beyond the Barcoo, which is further back o' Bourke than the back o' Bourke, but I was excited about approaching Bourke from the west, the more remote side of town, the official Outback, by mythological definition.

We were awake early in Hungerford, having gone to bed early. We planned to make our own breakfast en route. Graham had already left on the mail run: he must have been up well before 6. How much longer will he want to run a pub and be the mailman over large distances in a remote region? How long will he be able to do those things? The Outback is steadily being depopulated: the further west you go (from the east coast) the greater the distances between settlements whose populations are dwindling, as the young choose not to follow in their parents' footsteps.

There was another state border to cross. I'm not sure exactly what I expect when crossing a state border but I am usually disappointed, often because a plethora of signs detracts from any subtle landscape changes (except on the Lions Road – see Cor, Barney!, January 2014). This border post was a bit bleak, in the cloud, with its faded signage.

One can only imagine the original mileage on the sign for Bourke was 100 kilometres out! Google maps predicts it takes four hours to drive a little over 200 km; and someone had mentioned the track was hard-going. It was tricky in places but not particularly arduous, especially with plentiful stops. We wanted to be in Bourke for lunchtime latest so we would have half a day there. A large bank of cloud was moving into Queensland, and soon we had sunshine. The first stop wasn't long off.

The birds above were new to us – Banded Lapwings, two females and two males. They appeared to be rather nervous creatures.

There was more standing water. Kangaroos mustn't like getting their feet wet, as they were leaping over it, while emus splashed through, although I have noticed that they avoid creeks. Their running fascinates me: no body part north of their legs moves. What do kangaroos find to eat on arid plains, we pondered? Someone told us later in New South Wales that drought is forcing them ever closer to habitation in search of food.

Yantabulla seemed deserted and derelict, except for a fire station. I jumped out of the car to photograph corrugated remains, but was sickened by the stench of rotting flesh. There was something ugly decomposing by the roadside.

And then a real treat: loads of Major Mitchell's, so engrossed in their bush melon feast they completely ignored us.

All holiday, I had been trying to capture goats, photographically: finally I managed it. I know feral goats are eating their way through Australia's vegetation, and I should probably have been shooting them in the literal sense, but I like them far too much. I have no idea at all what the sign means in this context. If anyone knows, please enlighten me in a comment at the bottom of the page.

There were cows in the middle of the road; and dead dogs strung up by the side of it. We observed this custom last year, but I still don't get it. Is it meant to be a deterrent to other ferals? This is what'll happen to you, mate, if I find you on my property*. What is clear is that those who live back east have little grasp of the feral problem in the back blocks, or the vast numbers of methane-emitting cows thwarting Australia's emissions targets.

The pub in Fords Bridge had been recommended, but they couldn't supply a proper cup of coffee, even though it was coffee time. Most of their customers are workers who needed beer, not coffee, they explained. We drove on, but not before I'd studied vehicles growing in paddocks. We soon came across the Warrego River again. I think of it as a Queensland River, which it is, but it's also the northernmost tributary of the Darling, which it joins southwest of Bourke.

And so we reached Bourke, with its double excitement factor. Traditionally accredited with being on the edge of civilisation as defined by farming and settlement, it has the Back o' Bourke Exhibition Centre to prove it; and the town sits by the famous Darling River. On the outskirts of development, we came across our first white lines on the road for what seemed like ages: I was not pleased to see them, for they heralded the end of the Outback.

The town grew up from 1862 to supply surrounding pastoral properties and export their wool. Bourke was the centre of this industry for more than a century. Paddlesteamers plied the Darling; Cobb & Co passed through town; and horse, bullock and camel teams transported provisions for a thriving settlement. It was at its most prosperous at the end of the 19th century, before declining and then reviving since the 1970s when the cotton industry developed.

We were staying in North Bourke, five kilometres north of the town itself and on our way in, but it was too early to check in. We went to Diggers on the Darling – not surprisingly, an old RSL club – for a much-needed coffee, before crossing the road to take our first look at the Darling. Despite a troubled history, it still struck me as a majestic, deeply significant river. I have a plan to follow it southwest from Bourke as it wiggles its way to Wilcannia. The Darling continues from there to Menindee, then more south to Wentworth where it meets the mighty Murray. Meanwhile, I was mesmerised by the abundance of pelicans and other waterbirds.

The Darling is Australia's third-longest river (after the Murray and the Murrumbidgee). It's headwaters are in Queensland's Darling Downs, but it is fed by many tributaries, including the Barwon, Little Bogan, Culgoa, Warrego and Paroo. The river was obviously of crucial importance to the nation's first inhabitants, then later to explorers, settlers and pastoralists. But it hasn't always thrived. Its flow has long been irregular – it dried up 45 times between 1885 and 1960 – long before irrigators made such demands; and in 1992 an algal bloom extended throughout its length. Locks and weirs have been constructed since the end of the 19th century to regulate flow, improve navigability and store water either for consumption or to regulate flow downstream.

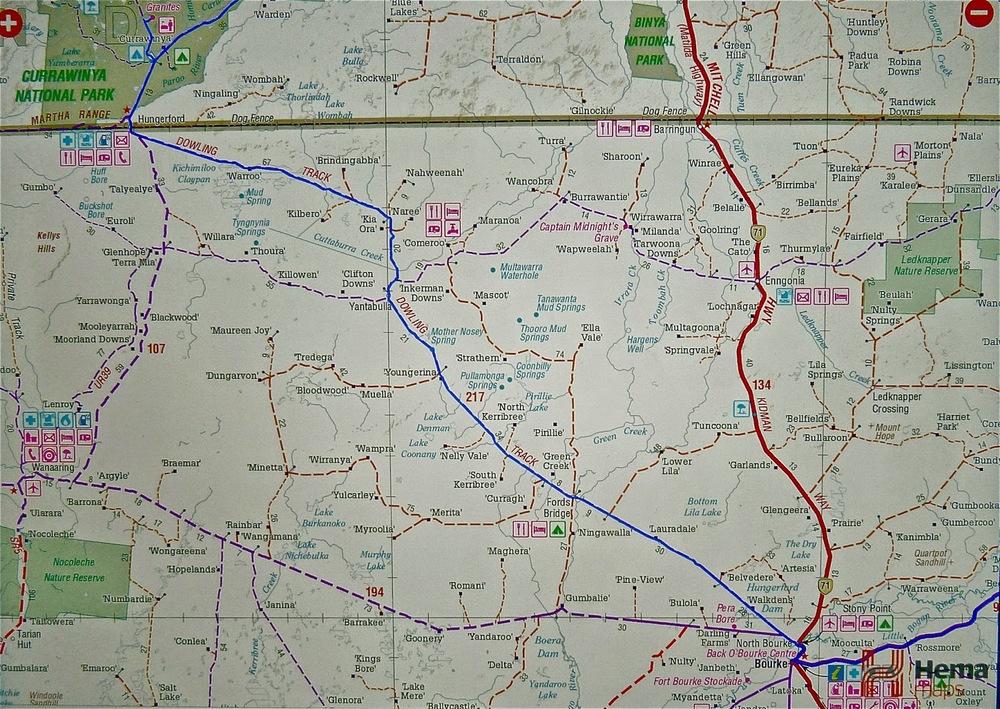

We wasted no more time before driving to the Back o' Bourke Exhibition Centre, which includes a visitor information office. I was looking for a t-shirt with the slogan 'I've been well back o' Bourke'. Needless to say, I didn't find it, and had to make do with a lousy sticker. We bought Hema's Outback New South Wales (because, despite the wonders of GPS tracking and iPad mapping, I love looking at a paper map when planning journeys); and The Penguin Henry Lawson Short Stories, the back of which claims: 'One of the great observers of Australian life, Henry Lawson looms large in our national psyche.' He frequently pops up in the history of Bourke.

The curved walls and flowing lines of the Exhibition Centre are intended to reflect the Darling, and the buildings are nicely designed. The founding of Bourke and the story of wool feature large. The exploits of explorers such as Charles Sturt and Sir Thomas Mitchell are chronicled, and concepts such as the early obsession with a vast inland sea, and differences in attitudes towards the land between Aborigines and settlers are explored. There are brilliant quotes, poems and personal anecdotes, because the Centre is a storytelling rather than an artefacts and reconstructions experience. If I were to be picky, I would say the volume of the audiovisual loops is too intrusive if you're after quiet contemplative reading. The Centre is well worth a visit nonetheless.

Bourke Land Board District, showing pastoral holdings circa 1885

We continued back along the road on which we'd come into town, to the Bourke Bridge Inn, right by the first bridge over the Darling. When we did our usual voting at the end of the trip for best accommodation, food, experience, etc, this place came out top accommodation. Our room in the main house (there are also cabins) was spacious, comfortable and well furnished; the lighting was good but not harsh; we had balcony on two sides; and, most importantly, we could see the bridge and the river. We spent some time on the bridge: my friend, being an engineer, had construction to study; I had photographs to take, the bridge lending itself so well. These activities were eventually curtailed by a storm, the first big clap of thunder making the pellies jump. Spectacular light and cloud are probably the only things that can distract me from my fear. The rain lent a softness to the riperian landscape.

There were many pellies, but, as the storm clouds gathered, they were being watched.

That evening, we returned, through rain, to Diggers on the Darling for an agreeable supper. It was, however, a real pleasure to return to our room. I still had many of the thoughts of explorers and pioneers in my head.

Charles Sturt wrote:

Let any man lay a map of Australia before him, and regard the blank upon its surface, and then let me ask him if it would not be an honourable achievement to be the first to place a foot at its centre.

And from Thomas Maslen, a former officer in the East India Company who famously produced a detailed map of the notional Inland Sea:

There is a mystery about the geography of Australia, which I venture to say has never had a parallel in any other country, and which is enough to excite the most extravagant curiosity in those whose studies have led them to a contemplation of the varied surface of our beautiful planet.

With thanks to the Back of Bourke Exhibition Centre for some inspirational quotes

* I have since been told that farmers string up the dead dogs to encourage their less conscientious neighbours to take more action about ferals.

This post was last edited on 4 November 2016