Dogs and coal

Last week I read about the social capital of owning dogs. Before I go any further, just in case you're not sure, social capital can be thought of as the links or connections, shared values and understandings in society that enable individuals and groups to trust each other and so be able to work together.

So, the article said that if you own a dog – actually, few Aussies own a dog; many have two or more – and you take it to the dog off-leash area and commune with your fellow dog-owners, and chat over takeaway coffees, few of them in keepcups I would guess, then you'll feel like a more valued member of your community and part of a network of shared interests that'll give you a warm glow long after you've walked home, put the dog in the yard, and gone inside.

I'm not sure, because I haven't done the research, what dog-owners think about non-dog-owners, like me. Do they think we're weird; we don't like animals; we prefer cats; we're worried about hairs on the furniture; we don't need the exercise; or we've got a budgie, rabbit, hamster, goldfish, tortoise, rat, snake, etc instead?

Maybe they don't think about it. They certainly don't seem to think about the effects of all their dogs on their non-dog-owning neighbours. I'm sure they don't consider little pooch's welcoming barks to be noise pollution, for example. Like I do.

We moved to where we live now last September. Before we signed the lease I sat outside in my car at different times over several days to assess the dog noise in the neighbourhood. I'd already spotted a dog kennel next door so I was worried its occupant wouldn't be as wise as Lab next door to our old house, who only spoke – a single significant woof – when he had something of import to say. We liked Lab: he was a good neighbour. But here? Ye gods, it's like living in a dog pound. I don't know how they all kept quiet when I did my research. There must be at least one dog in every house, either side of us and across the road. Every variety you can think off: irritating little white yappers; big unruly howlers; and ugly, inbred psychos that are highly strung at best. One street over, immediately behind our group of four town houses, there are two properties with seven dogs between them. They're the principal architects of the dog-pound effect. Each group of dogs sets off the other, and their combined noise has to be heard to be believed. It's way beyond noise pollution. The four little white yappers at one house have woken us in the night, when I would happily kill them if I could be bothered to get up and walk around the block. When I went to complain, their owner pleaded with me not to report him to Council. I suspect he doesn't have the permit required to own more than two dogs.

Do dog-owners become largely immune to dog noise over time? How can they possibly think it's acceptable that I should have to put up with it, while they're at work having left their animals in the yard all day, and all night in summer? Do they think dogs sit quietly waiting for them to come home, and don't bark at passing schoolchildren, posties, other dog-walkers, or tradies working next door? Perhaps they cannot imagine how wearing and stressful it is to hear fairly constant barking, day after day.

Even if the dogs are inside, you can hear them because most Australian houses are poorly insulated – against heat, cold, noise, whatever.

And then there are the dog owners who consider themselves above the law that says dogs must be on leads in public spaces. They walk along, lead in hand but not attached to a dog, because of course their dog is so well behaved it won't run at anyone, jump up, lick, growl, bite, and frighten those of a delicate disposition. If you point out that you're in a national park and dogs are not allowed in there at all, you are either verbally abused or on the receiving end of a sarcastic comment that implies you're a moaning killjoy rather than a wildlife protector.

So what's the social capital factor for those who don't own a dog but have to put up with the effects of those who do?

Living in Australia has made me dog-intolerant.

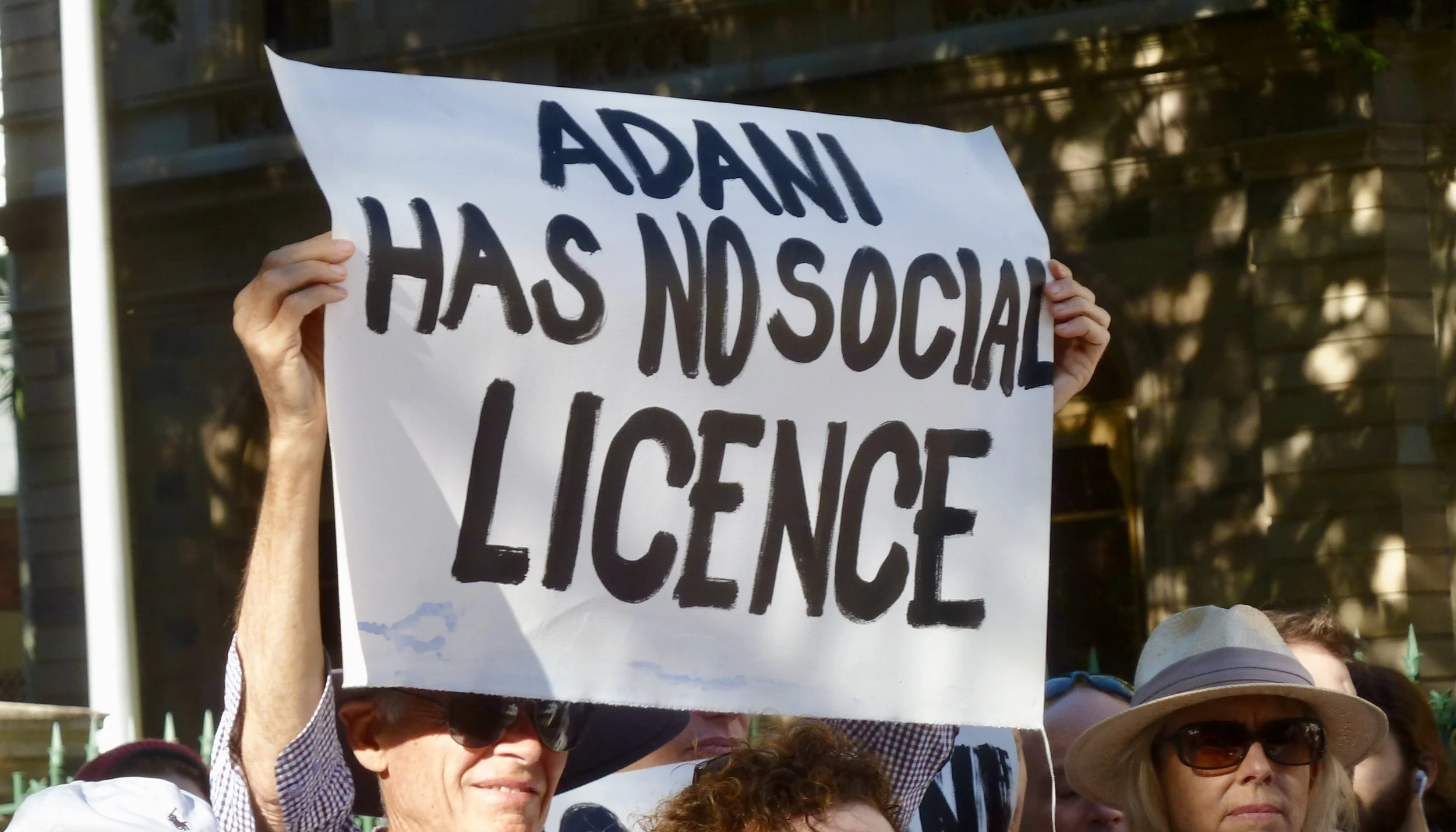

And then there's social licence, or, sometimes, social licence to operate (SLO, because we have to turn everything into an acronym, which of course, technically, this is not). This generally describes the informal tacit acceptance or approval by a community, or wider society, of governance on their behalf. Specifically, SLO usually refers to infrastructure projects or resources development.

When a governing body is elected, it will usually have set out its policies, and the votes it receives are considered a mandate to implement those policies. Sometimes, of course, events dictate that new policy must be created. Government must then assess the current mood or opinions of the people in order to pass new legislation that will be acceptable without a vote.

In Australia, legislation concerning mining was put in place in 1989, in the Mineral Resources Act. Then there were only mutterings about climate change, and the Great Barrier Reef was pristine and remarkable. Unfortunately, in the vastly different world of 2017, law that allows a permit to mine without due consideration of the complete range of impacts seems woefully inadequate.

In the case of Adani's Carmichael mine in Queensland's Galilee Basin, the company was not obliged to calculate carbon emissions beyond the mine site operations and the transportation of coal to port; its ecologists did not have to estimate the value of the core population of endangered Black-throated Finch; and it economics expert did not have to weigh up the benefit of new mining jobs against the loss of existing jobs in farming or tourism. No one knows precisely what will happen to the Great Artesian Basin when the mine uses vast quantities of water every day because knowledge of the hydrogeology of the region is sketchy at best.

It's hardly surprising, therefore, that millions of Australians are voicing their concern for the Reef, potential climate chaos, and the depletion of water for farming. They want greater development of renewable energy rather than fossil fuels. They know their country signed up to emissions reduction targets in Paris, and believe these should not be ignored by politicians in the pay of resources companies.

I know the man holding up the placard at the top of the page. He's not a 'Greenie' or a left-wing extremist or a hippie or a Communist: he's the grandfather of a little girl who's set to inherit an unclean unpleasant land if he doesn't speak up. His government is not listening, and hopefully sooner rather than later they will pay the price.